- Home

- JOIN

- History

- Maps

- Treaty Forums

- Purpose of the Peace Treaty Forums

- Forum I Jun 1994

- Forum II Oct 1994

- Forum III Sep 1995

- Forum IV Mar 2000

- Forum V Dec 2006 TR Nobel 100th

- Forum VI Dec 2007 with Dennis Ross

- Forum VII Dec 2008 with Samantha Power

- Forum VIII Dec 2009 Obama's Nobel

- Forum IX Nov 2016 Russia-Japan

- Forum X Nov 2019 Jake Sullivan

- Forum XI Sep 2020 Joseph S. Nye Jr.

- Citizen Diplomacy

- Connections

- Spiritual Aspects

- 2005 100th Anniversary

- 2006 Nobel Prize 100th

- 2007 Commemorations

- 2008 Commemorations

- 2009 Commemorations

- 2010 Portsmouth Peace Treaty Day

- 2011 Order of the Rising Sun

- 2012 100 Years of Cherry Trees

- 2013 Historic Marker Dedicated

- 2014 Sister City Celebrations

- 2015 110th Anniversary

- 2016 Commemorations

- William Chandler & Concord, NH

- Kentaro Kaneko & Dublin, NH

- Asakawa, Dartmouth & Hanover NH

- Carey Family & Creek Farm

- Henry Denison & Lancaster, NH

- John Hay & Newbury, NH

- Japanese Visit Manchester, NH

- Wentworth & New Castle, NH

- Portsmouth: Temple Israel, Rev. Clark

- Sarah Farmer & Eliot, Maine

- Adm. Mead & Kittery, Maine

- Elizabeth Perkins & York, Maine

- Educational Resources

- Living Memorial Project

- Contact Us

- 1713 Treaty

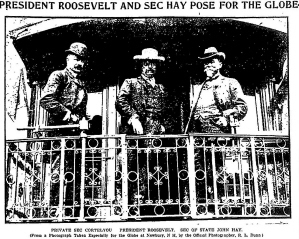

Theodore Roosevelt's Secretary of State John Hay

The Fells, Newbury

In August 1902, on a Presidential tour of New England, Roosevelt stayed overnight with the Hays at The Fells. Newspapers report that Hay met him at the depot in Newbury and they crossed Lake Sunapee in the Hays’ private steam launch, The Nomad. During his visit, Roosevelt planted a maple tree, that endures (below).

The Roosevelt maple frames a view of The Fells.

The Roosevelt maple frames a view of The Fells.

The Fells, Hay’s home (top) and gardens with view of the lake (above).

The President stayed in this second floor bedroom (above) during his visit.

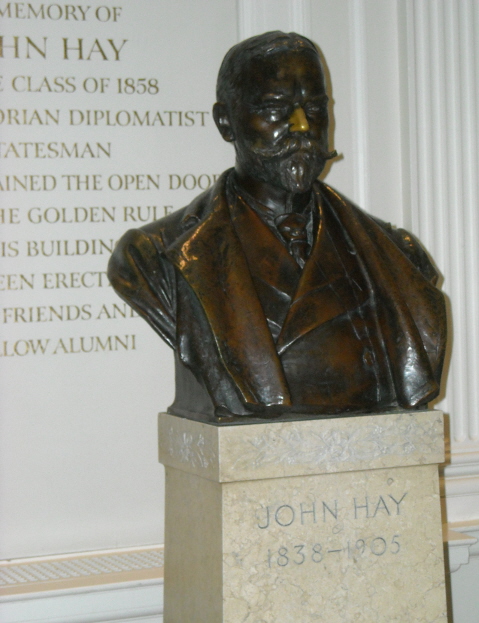

JOHN MILTON HAY (1838-1905)1838, Oct. 8 Born, Salem, Ind.

1858 Graduated, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

1859 Entered law office of Milton Hay, Springfield, Ill.

1861-1864 Assistant private secretary to Abraham Lincoln

1864-1865 Assistant adjutant general in the United States army

1865-1867 Secretary of American legation, Paris, France

1867-1868 Charge d’affaires, Vienna, Austria

1869-1870 Secretary of American legation, Madrid, Spain

1870-1875 Editorial writer, New York Tribune

1874 Married Clara Louise Stone (died 1914)

1879-1881 Assistant secretary of state

1881 Editor, New York Tribune

1897-1898 Ambassador to Great Britain

1898-1905 Secretary of state

1905, July 1 Died, Lake Sunapee, N.H.

Bronze bust of John Hay by Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

The gift of Mrs. Hay to the John Hay Library at Brown University.

John Hay was the behind the scenes author of so much of the

Secretary of State John Hay in his office in the War Department.Roosevelt visited him often here. as Diary references such as this one from February 3, 1905 notes,"The President spent an hour with me in the afternoon. He was deeply disturbed about the state of the treaties in the Senate, not so much at the opposition of the Democrats as at the nerveless acquiescence of our people in every attack that is made upon them"

At the age of 59 and after years as internationally acclaimed author, editor and statesman (as well as

The President made a habit of stopping at Hay’s home (above) at 800 16th Street, across Lafayette Square from the White House every Sunday after church for a chat before lunch. In a campaign speech at Carnegie Hall in October 1904 Hay had asserted, "He [TR} and his predecessor have done more in the interest of universal peace than any other two Presidents since our Government was formed.’" Roosevelt, in April 1903, after calling Germany’s bluff over Venezuela – all completely off the record – wrote to Hay, "I wonder if you realize how thankful I am to you for having stayed with me. I owe you a great debt, old man." In July 1903, in reply to Hay’s offer that he step aside as Secretary of State to make way for Elihu Root (the man TR would choose to succeed Hay two years later) Roosevelt declined, saying "As Secretary of State you stand alone. I could not spare you."

In August 1902 when President Roosevelt visited his Secretary of State at The Fells in Newbury, New Hampshire, the United States was emerging on the world stage, playing a part in negotiations affecting Alaska, Venezuela, the Panama Canal, the Philippines, China and Korea. Russia and Japan were drawing closer to the confrontation that would erupt in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-05.Hay was a critical source of guidance in the months leading up to the war and at the beginning of Roosevelt’s role in orchestrating an end to the conflict. Hay died at The Fells on July 1, 1905 before the peace conference between Russia and Japan began at Portsmouth, NH in August. But Hay’s advice and counsel prepared Roosevelt for his unique, international, multi-track diplomacy which resulted in successful negotiations concluding with the Portsmouth Peace Treaty that ended the war and earned Roosevelt the Nobel Peace Prize. John Hay’s diaries detail the ambassadorial contacts and initiatives he and President Roosevelt made as they tried to bring the other Powers, including Russia and Japan, to consensus in recognizing China’s "administrative authority" -- the main issue behind the dispute between Russia and Japan over Manchuria.

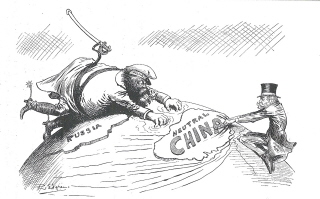

THE DIPLOMACY

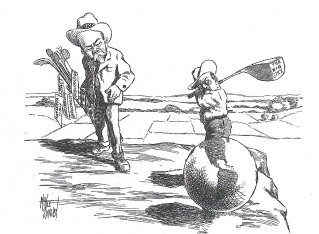

With McKinley’s Cabinet, Roosevelt gained the wisdom and diplomatic experience of Hay, as his Secretary of State. The cartoonist McKlee Barclay portrayed the opinion of many around the country following the assassination of President William McKinley. In the cartoon (left), Roosevelt is shown wielding his famous "big stick" as a golf club, with the world as his ball. Hay stands ready with clubs named "diplomacy," "tact," conservatism," "statesmanship" and "arbitration." The caption that accompanied the cartoon reads, "A would-be champion. who is somewhat erratic, labors under the disadvantage of wielding a very large stick, and insists on playing with a big ball, but they say his caddy is fine and will pull him through."

© Copyright 2005 Japan-America Society of New Hampshire

NH Web Design | Content Management | Web Hosting