- Home

- History

- Maps

- Treaty Forums

- Purpose of the Peace Treaty Forums

- Forum I Jun 1994

- Forum II Oct 1994

- Forum III Sep 1995

- Forum IV Mar 2000

- Forum V Dec 2006 TR Nobel 100th

- Forum VI Dec 2007 with Dennis Ross

- Forum VII Dec 2008 with Samantha Power

- Forum VIII Dec 2009 Obama's Nobel

- Forum IX Nov 2016 Russia-Japan

- Forum X Nov 2019 Jake Sullivan

- Forum XI Sep 2020 Joseph S. Nye Jr.

- Citizen Diplomacy

- Connections

- Spiritual Aspects

- 2005 100th Anniversary

- 2006 Nobel Prize 100th

- 2007 Commemorations

- 2008 Commemorations

- 2009 Commemorations

- 2010 Portsmouth Peace Treaty Day

- 2011 Order of the Rising Sun

- 2012 100 Years of Cherry Trees

- 2013 Historic Marker Dedicated

- 2014 Sister City Celebrations

- 2015 110th Anniversary

- 2016 Commemorations

- William Chandler & Concord, NH

- Kentaro Kaneko & Dublin, NH

- Asakawa, Dartmouth & Hanover NH

- Carey Family & Creek Farm

- Henry Denison & Lancaster, NH

- John Hay & Newbury, NH

- Japanese Visit Manchester, NH

- Wentworth & New Castle, NH

- Portsmouth: Temple Israel, Rev. Clark

- Sarah Farmer & Eliot, Maine

- Adm. Mead & Kittery, Maine

- Elizabeth Perkins & York, Maine

- Educational Resources

- Living Memorial Project

- Contact Us

- 1713 Treaty

Jacob Schiff Visits Witte at Wentworth

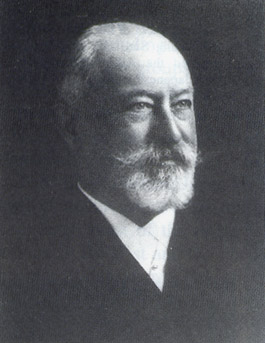

Jacob Schiff was the head of the international banking concern Kuhn, Loeb & Co. in

Jacob Schiff was the head of the international banking concern Kuhn, Loeb & Co. in

Recalling the meeting with Witte to the national B’nai B’rith assembly, Adolph Kraus commented that in 1905 some members of the American Jewish community thought that their complaints to the Czar should be more deferential, while others felt the time was now to take a more forceful stand. Clearly Schiff, whom Witte described as pounding on the table in the room at Wentworth By the Sea where they met, took the more radical position.

Over the past two years, Kirill Finkelshteyn, a recently arrived Russian in

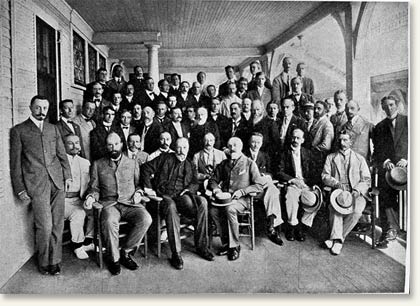

Gregory Vilenkin pictured, seated to left, behind Witte.

At one point in the Wentworth meeting Schiff pointed to Vilenkin (who acted in Portsmouth as Witte’s interpreter) and said to Witte, “Will you please tell me why you as a Russian have all the rights in that country which are given to any one and why this man has no rights whatsoever?” According to Kraus, who reported the meeting in the Bnai Brith Annual Report and Korostovetz who recalled the meeting in his diary, the immediate result was what the Jewish delegation sought: that Witte would relay their message to the Czar.

Three days after the meeting, Kraus received a letter from Vilenkin saying, “I am officially instructed by his Excellency Mon de Witte to inform you and the gentlemen who met him with you, that after your departure he cabled to St. Petersburg … to inquire whether any changes were made … concerning ‘the rights of the Jews to elect and be elected in the proposed National Assembly.’ His Excellency received by cable answer that… Jews will have the same right as the rest of the population to elect and be elected in the National Assembly.” In October 1905, as Prime Minister of Russia (and after earning the title of Count for concluding the Portsmouth Peace Treaty in September), Witte convinced the Czar to accept the “four freedoms” Manifesto to end the mass workers’ strike and moderate the government’s harsh treatment and denial of human rights.

© Copyright 2005 Japan-America Society of New Hampshire

NH Web Design | Content Management | Web Hosting