- Home

- History

- Maps

- Treaty Forums

- Purpose of the Peace Treaty Forums

- Forum I Jun 1994

- Forum II Oct 1994

- Forum III Sep 1995

- Forum IV Mar 2000

- Forum V Dec 2006 TR Nobel 100th

- Forum VI Dec 2007 with Dennis Ross

- Forum VII Dec 2008 with Samantha Power

- Forum VIII Dec 2009 Obama's Nobel

- Forum IX Nov 2016 Russia-Japan

- Forum X Nov 2019 Jake Sullivan

- Forum XI Sep 2020 Joseph S. Nye Jr.

- Citizen Diplomacy

- Connections

- Spiritual Aspects

- 2005 100th Anniversary

- 2006 Nobel Prize 100th

- 2007 Commemorations

- 2008 Commemorations

- 2009 Commemorations

- 2010 Portsmouth Peace Treaty Day

- 2011 Order of the Rising Sun

- 2012 100 Years of Cherry Trees

- 2013 Historic Marker Dedicated

- 2014 Sister City Celebrations

- 2015 110th Anniversary

- 2016 Commemorations

- William Chandler & Concord, NH

- Kentaro Kaneko & Dublin, NH

- Asakawa, Dartmouth & Hanover NH

- Carey Family & Creek Farm

- Henry Denison & Lancaster, NH

- John Hay & Newbury, NH

- Japanese Visit Manchester, NH

- Wentworth & New Castle, NH

- Portsmouth: Temple Israel, Rev. Clark

- Sarah Farmer & Eliot, Maine

- Adm. Mead & Kittery, Maine

- Elizabeth Perkins & York, Maine

- Educational Resources

- Living Memorial Project

- Contact Us

- 1713 Treaty

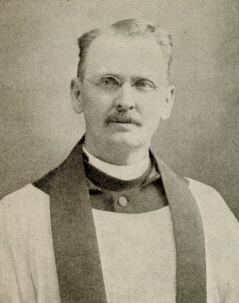

Promoting Japan in America: the Life Work of E. Warren Clark (1849 – 1907)

by Richard M. Candee

Edward Warren Clark (right) was a nineteenth century American educator, journalist, amateur photographer, Episcopalian minister, cultural entrepreneur and self-promoter. His life’s work began when he was hired from 1871-75 by the Japanese government to teach thousands of young Japanese students the rudiments of modern science. Japan remained at the center of his life and dreams for the next thirty years.

Edward Warren Clark (right) was a nineteenth century American educator, journalist, amateur photographer, Episcopalian minister, cultural entrepreneur and self-promoter. His life’s work began when he was hired from 1871-75 by the Japanese government to teach thousands of young Japanese students the rudiments of modern science. Japan remained at the center of his life and dreams for the next thirty years.

He was born in 1849 in the old Mark Hunking Wentworth mansion on Daniel Street, Portsmouth, N.H. and lived there until he was six. His father, Rufus W. Clark, was the anti-slavery Congregational minister at North Church. When the family left for East Boston in 1855 that “fine old mansion,” with its spacious and “aristocratic” rooms, was deemed “dull and gloomy” and razed to build a new High School. An accident in boyhood severely damaged Edward’s eyes, requiring surgery. This handicapped Clark “all his life and caused much retardation to an otherwise energetic person.” In 1860 New York City the 11-year old saw the pioneering Japanese Embassy ride up Broadway in a dazzling procession with 7,000 welcoming troops that left a lasting impression.

Clark would graduate from what is now Rutgers University in New Jersey in 1869 with a degree in Chemistry and Biology. While there he gained the lasting friendship of several prominent Japanese students, a son of province Governor Okubo Ichio, and Iwakura Tomomi. These students and other Japanese visited his home in Albany and attended his father's church.  After a post-graduate summer in Switzerland with Rutgers classmate William Elliott Griffis (1842–1928) Clark, who stayed on to study for the ministry, joined Griffis as the first Americans to introduce western science and technology to the Japanese classroom. When Clark arrived in October 1871, Okubo, Tomomi, Admiral Katsu Kaishu (whose name Clark wrote as Katz Awa) and other prominent officials welcomed him. (By December Tomomi left to lead the Japanese embassy to the United States.) Correspondence between "Clarkie" and "Griff" -- who later taught at Cornell as one the first American academic Japanologists -- as well as the memories of Clark's man-servant Sentaro (nicknamed Sam Patch) add perspective and detail to Clark's own published work about his life. Clark’s letters to his friend “Griff” are a major source of information about his life and beliefs.

After a post-graduate summer in Switzerland with Rutgers classmate William Elliott Griffis (1842–1928) Clark, who stayed on to study for the ministry, joined Griffis as the first Americans to introduce western science and technology to the Japanese classroom. When Clark arrived in October 1871, Okubo, Tomomi, Admiral Katsu Kaishu (whose name Clark wrote as Katz Awa) and other prominent officials welcomed him. (By December Tomomi left to lead the Japanese embassy to the United States.) Correspondence between "Clarkie" and "Griff" -- who later taught at Cornell as one the first American academic Japanologists -- as well as the memories of Clark's man-servant Sentaro (nicknamed Sam Patch) add perspective and detail to Clark's own published work about his life. Clark’s letters to his friend “Griff” are a major source of information about his life and beliefs.

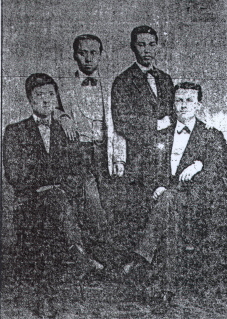

Clark and Japanese students c.1872-75

Clark taught first at a large school in Shizuoka (that he spelled Shid- zu-oo-ka), where he trained students to become science teachers. A devout Christian, Clark introduced the Bible and established Sabbath Schools for his Japanese students. An occasional journalist, Clark served as Japan correspondent for his college paper, the Rutgers Targum, and religious newspapers like the New York Evangelist and The Child’s Paper.

In 1873 he was transferred to the Imperial University (later Tokyo University), to help found the chemistry department, one of the first of its kind in Japan. Griffis, too, was in Tokyo and wrote his magnum opus The Mikado’s Empire [1876] in Clark’s Tokyo home.

Clark's home in Tokyo, Japan.

Clark's home in Tokyo, Japan.

Clark, as a scientist and explainer of western technology, took and developed photographs of Japan and later, scenes from his 1875 return trip to the United Stated by way of China, India, and Palestine. He presented a special illustrated lecture for the Mikado at the emperor’s palace in Tokyo.

Ministry and Marriage

Back in the US, Clark combined his old published stories and personal photographs into Life and Adventure in Japan, published by the American Tract Society in 1878. A second volume, From Hong-Kong to the Himalayas: or, Three thousand miles through India appeared in 1880. Japan, the Orient, the Holy Land, and “Around the World in Eighty Minutes," soon became the subjects of hundreds of popular lectures that Clark offered 1876 to 1878 while he studied for the ministry in New York and Philadelphia.

Back in the US, Clark combined his old published stories and personal photographs into Life and Adventure in Japan, published by the American Tract Society in 1878. A second volume, From Hong-Kong to the Himalayas: or, Three thousand miles through India appeared in 1880. Japan, the Orient, the Holy Land, and “Around the World in Eighty Minutes," soon became the subjects of hundreds of popular lectures that Clark offered 1876 to 1878 while he studied for the ministry in New York and Philadelphia.

In 1879 while serving the Church of the Ascension in Steven’s Point, Wisconsin, he married Louise McCulloch, the daughter of successful local businessman and banker. In 1883 he was assigned to Tallahassee, Florida where his wealthy father-in-law McCullough purchased a 900-acre plantation that Clark and a Philadelphia partner bought and renamed “Shid-zu-oo-ka” after the town in Japan where he first taught.

Clark's 1880 book on his travels.

Over the 1890s he transformed the plantation into an unsuccessful dairy farm and later opened it as a game preserve. For the next six years he fulfilled ministry assignments in Philadelphia, Alabama, Tennessee and Texas while also dabbling in real estate. In the summer of 1893 he was also involved in exhibiting the famous captured Confederate locomotive, “The General” at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

‘Clark’s Oriental Tours’

In 1891, he started to plan a return to Japan, leading a group tour of a dozen people to cover all his travel costs. In July 1892, Clark presented a series of illustrated lectures at the Rockford, IL Opera House, beginning with "The Mikado's Court" about his four years in Japan. In March 1894 he invited a “Prof. Satoh,” (who according to the Rockford Daily Register and Gazette was a Japanese representative with the Exposition in Chicago), probably the Aimaro Sato who later served as press secretary to the Japanese delegation attending the peace conference in Portsmouth, to speak in Rockford on “Social Life in Japan.”

In 1894 Clark got a new passport; it shows the clergyman as 45 years old, 5 foot 8 inches high, with blue eyes, auburn hair, and a round face, high forehead and straight nose. When he, one Rockford widow and seven “eastern people” left Chicago for Hawaii, the Philippines, and Japan, his hometown paper said, “It would be difficult to find a better guide through Japan than Prof. Clark, as he was in the Mikado’s service for four years, and has traversed the empire . . . , being better acquainted than many of us are with the United States.” He led another tour to Japan the next year.

While revisiting Japan with his 1894 tour, he met with a man he pronounced “Katz Awa” [now Katsu Kaishu] (1823-1899), who had founded the modern Japanese Navy, and he returned to the U.S. with his brief autobiographical memoir. He later tried to interest Harper Brothers in publishing the memoir, but they felt it was too short for a full book.

While revisiting Japan with his 1894 tour, he met with a man he pronounced “Katz Awa” [now Katsu Kaishu] (1823-1899), who had founded the modern Japanese Navy, and he returned to the U.S. with his brief autobiographical memoir. He later tried to interest Harper Brothers in publishing the memoir, but they felt it was too short for a full book.

Next: Travel & Tragedy

© Copyright 2005 Japan-America Society of New Hampshire

NH Web Design | Content Management | Web Hosting